Inside the Dreamcast

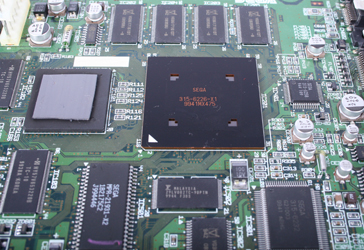

Inside the white plastic, and beneath the iconic swirl, sits a punchy set of hardware for the time which, believe it or not, was surprisingly PC-like in many areas. While the Dreamcast was an undoubted flop, ending Sega’s efforts as a console manufacturer, the platform itself was very much ahead of it’s time.At the core of it all was Hitachi’s “Super-H” SH4 processor, which ran at 200MHz - about normal for 1998 when CPUs such as the Pentium II were only just stretching from 233MHz to 450MHz.

What set the SH4 apart from other CPUs of the era was that it was specifically designed to be efficient and operate with minimal power consumption. At 1.5W it only needed a tiny heatsink with no fan, cutting manufacturing costs and removing a potential failure point that modern consoles struggle with. There's no 300W power brick and Red Ring of Death for the Dreamcast, which already puts it ahead of most current consoles.

It’s unsurprising that Sega went to Hitachi for its CPU; it had previously used Super-H chips in the Sega Saturn and since both companies are Japanese it inevitably made communication and co-operation between departments easier. Sega was obviously hoping that sticking with a familiar tech-base would mean the games could fly out much quicker too, with Saturn developers already familiar with a very similar hardware set.

On the super-technical end; the SH4 used its own reduced instruction set (RISC) in a simple five stage pipeline. The superscalar design could fire out (at most) two 16-bit instructions to the execution engine, which featured integer and floating point calculations, load/store operations and branch operations. Like we said – technical! It’s also worth noting that, while the SH4 claimed 1.4Gflops, the CPU couldn’t realistically handle it due to a very limited cache size.

The CPU was deemed a 32-bit processor, despite its 64-bit floating point engine and 128-bit vector engine, since official designation is decided by integer size, which was 32-bit. The vector unit was particularly powerful and was essentially a co-processor to the (as then) NEC/Videologic PowerVR graphics chip, calculating the geometry for it.

Sega had also reportedly worked with 3dfx to design an alternative to the PowerVR. At that time Microsoft was putting an early DirectX API into a specifically coded variant of Windows CE (which eventually ran the console); 3dfx’s Glide API was a competitive, not co-operative choice. The rumoured alternative never came to be.

The Dreamcast’s tile-rendering approach was also of note for the way it allowed the vector unit within the CPU to generate the triangles before the PowerVR GPU converted and stored them as a triangle strip. The display output was then split into a grid and each tile was associated with a list of the triangles that visibly overlapped that tile, before the tile was rendered. It was an approach that forwent the Z-buffer culling and hierarchical Z-buffering that was later developed for removing unseen polygons.

Some games at the time greatly preferred this approach to rendering and it worked for the Dreamcast. However, PowerVR never really kept up with driver and compatibility updates compared to the competition, and the PC hardware the company made was never in high demand. These factors possibly impacted the success of the company and, as a result, the Dreamcast.

Either way, the graphics system of the Dreamcast was sufficient to compete with the Voodoo 2s and ATI Rage cards of the time, which made the Dreamcast formidable competition for most PCs of the period, and enough to put Sony’s PlayStation 1 to shame.

Unfortunately though, the Dreamcast arrived just before a major change in graphics hardware, when new transform and lighting (T&L) systems were developed. Developers rushed to make use of the new techniques, leaving the PowerVR chip of the Dreamcast behind. These days PowerVR hardware is usually found in very low power, handheld hardware rather than high end games consoles. In theory (and with the right coding) you could run a Dreamcast game on a mobile phone such as the iPhone!

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.